I received this email today from James Barlow. I have decided to share here on North Devon Angling News website because I share the concern regarding salmon farming and its devastating impact upon salmon, sea trout stocks and the wider impact this has on the environment. I have visited the West Coast of Scotland and talked to local people who have witnessed the dramatic decline in salmon and sea trout numbers. We have seen dramatic declines in the West Country but not as rapid as seen in parts of Scotland. In Norway I caught cod and halibut with their stomach contents packed with pellets. The water on calm nights shimmered with oil that I believe came from the waste from these farms. The cod and coalfish we caught were also carrying large numbers of lice.

As anglers we all care for the long term future of fish stocks for we have a vested interest in one sense in that we want to catch fish but also because anglers care about fish and the environment in which fish live.

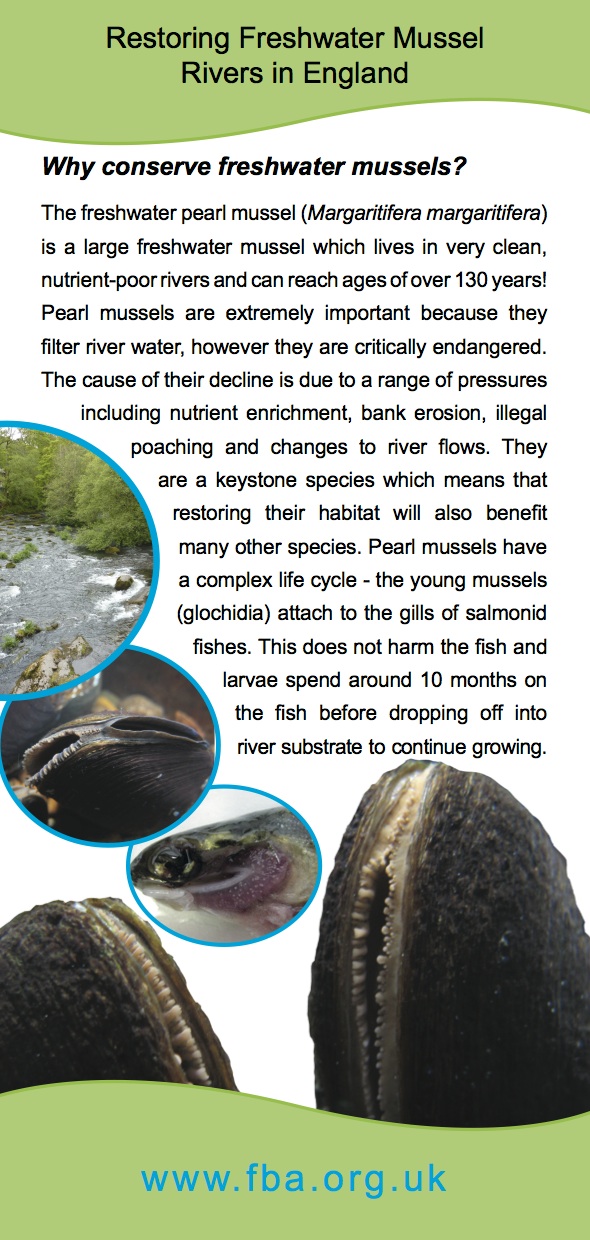

This July I assisted in the rescue of 75 salmon from a local estate after over 100 wild fish had already died. We believe the deaths were exacerbated, if not caused, by lice infestation from local salmon farm cages in Loch Roag, Isle of Lewis. The regional Fishery Trust biologist recorded between 500 and 700 sea lice, a parasite, on several live fish between 5-8 lbs. These wild fish are literally being eaten alive. My photos from the first day can be viewed here.

‘The One Show’ episode is available to watch on iPlayer until 18/10/18. The relevant article commences at 3 mins 10 seconds and runs for 9 minutes.

They highlight the plight of farmed salmon in cages which, like the wild fish, are suffering from appalling predation by lice. Last year, of the 208 salmon farms in the UK, 82 farms declared that they had exceeded the statutory Government acceptable limits for sea lice – that is 39.4% of all UK salmon farms.

Due to transportation costs, for the past two years the Scottish Salmon Company, proprietors of the farm in Loch Roag, has been burying thousands of dead fish (morts) in a ‘temporary’ landfill site in North Uist.

In the summer of 2017 over 175000 fish died of disease or attempted treatment at salmon farms in the Hebrides (The Telegraph). If this mort rate, or the effect of their farming methods on wildlife, were to occur to a mammal or on land the public outcry would be deafening, I’m sure. On average Scottish fish farms expect a mortality rate of around 23% of their stock. Such a high death rate would not be tolerated in any other form of animal husbandry.

Please take the time to view the programme and decide for yourself whether this is a quality product which you are happy to eat or serve to your family. Even ‘organic’ salmon can be treated with antibiotics yet still receive certification. EU regulation states that, “chemically synthesized allopathic veterinary medicinal products including antibiotics may be used where necessary…”. While ”excessive” treatment can result in removal of the prestigious Organic certification fish may still be treated under veterinary guidance then sold as ‘Organic’. Standard farmed salmon are regularly dosed in an attempt to ameliorate their condition. When you watch the video it will be clear why this is necessary.

Thank you for taking the time to consider this request. If you have any questions I will endeavour to answer them to the best of my ability.

Further video and photographic evidence can be viewed via this link to a Salmon Fishing Forum thread – ‘Sad, Sick Salmon both Farmed and Wild’. My contributions are under the username ‘Lewis.Chessman’.

If you feel sufficiently moved, please forward this mail to your friends and family. This industry will not change its methods unless its profits are threatened by consumer pressure.

My thanks to you all,

James Barlow.

The shortest day has been and gone and we have that interlude before the New Year gets underway; though nature has already turned the corner ahead of mans timelines. The last few days have seen benign weather; mild and damp with misty days. This passing of the year can be a time for contemplation and I often cast my mind back to winters of the past and in particular days and nights spent beside the water.

The shortest day has been and gone and we have that interlude before the New Year gets underway; though nature has already turned the corner ahead of mans timelines. The last few days have seen benign weather; mild and damp with misty days. This passing of the year can be a time for contemplation and I often cast my mind back to winters of the past and in particular days and nights spent beside the water.