I joined Dulverton Anglers Association in 2023 intending to explore the waters of the Exe and Barle that wind their way through the wooded valleys around Dulverton. As is often the case ambitions are not always met and I failed to make a single trip to their waters in 2023. We do however visit Dulverton on a regular basis and generally call into Lance Nicholson’s Tackle and Gun Shop to talk of the river or buy a few flies.

Having already sorted my 2024 subscription I was determined to start exploring their waters and pledged to pursue the grayling of the Exe and its tributaries as soon as conditions allowed.

Grayling are true fish of the winter months and give a great excuse to visit the water. The South West is not known for its prolific grayling fishing with just a handful of rivers supporting stocks of these enigmatic fish often referred to as the ladies of the stream.

The grayling of these Exmoor streams have been lingering in my mind for many years. Several decades ago, my wife and I attended a fishing event at the Carnarvon Arms. The Carnarvon Arms was a renowned Country Hotel that hosted many visiting anglers and country sports enthusiasts. A stand at the event was hosted by an elderly gentlemen who talked of grayling enthusiastically and fondly. Sadly, the Carnarvon Arms has now been converted into flats its legacy now just a distant and fading memory.

Fortunately, time has been kind to these rivers and whilst the salmon are in steep decline there is an everlasting and deep character that still flows. Negley Farson waxed lyrical about the Exmoor waters in his classic tome ‘ Going Fishing’.

“ I think the best thing to call it is a certain quiet decency. This almost unchanging English scene, with its red and green rolling hills, holds a romance that wild rocks, and wild flowers, or snow capped volcanoes could never give you. It has a gentleness, a rich rustic worth, and an unostentatiousness that is like the English character. An imperturbable scene which fills you with contentment.”

These streams are still inspiring authors to this day with Michelle Werrett’s latest book ‘ Song Of The Streams’, maintaining a rich literary vein that links the past to the present.

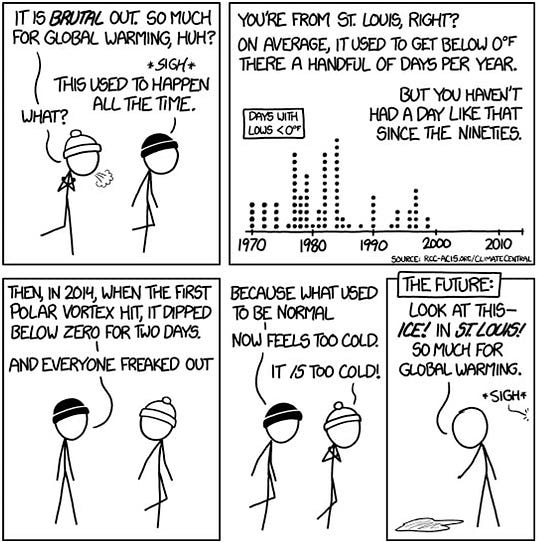

It was -5 degrees when I left home to drive across Exmoor. There was no hurry as I left home at around 9:30 hoping that the worst of the ice would have melted. The sun was well up in the sky as I drove across Winsford Hill yet the road glistened with white frost.

I arrived at Dulverton at around 10:30 and called into Lance Nicholson’s to get detailed instruction where to park to access my chosen beat on the River Haddeo. I purchased a hot pasty in Tantivy’s; a shop and café that I assume gained its name from the late Captain Tantivy an old English squire who rode with the hunt as mentioned in Farson’s “Gone Fishing’.

At the fishing hut I assembled my tackle whilst munching on a Cornish pasty and hot sweet coffee from my flask. I set off to the river unsure of the route to take. The Haddeo starts its journey high on the Brendon Hills its route punctuated by Wimbleball Reservoir that has become a mecca for Stillwater trout fishers.

The beat I was to fish runs through a Private Country estate and walking across the frosty field to the water I heard the volleys of shots from the shoot. The convoy of guns vehicles were parked up in the field across the valley. The pickers and their dogs worked away further up the valley and a team of beaters were undoubtedly working the woods and cover beyond.

The river was running fairly low and clear. I descended into the cold water carefully negotiating the barbed wire that will rip waders whatever the price tag!

And so, the search began with two gold headed nymphs carefully flicked into the rushing stream. It is a delight to explore a new water especially if it is wild and characterful as this beat is.

As I waded upstream a gamekeeper attired in traditional tweeds wandered across the field and made a friendly enquiry as to my success. I explained that it was my first visit to the water and that I hoped to catch a grayling. I don’t know if he was a fisher but he gave me encouragement telling me that there were some lovely looking pools up through the river valley.

I waded on clambering through the arch made by an ivy clad fallen tree. Icicles gripped the branches as they caressed the clear and icy water.

The river tumbled over a stony bed meandering through the valley. The signs of pheasant rearing were all around and I caught the occasional whiff of cordite from the shoot drifting in the cold frosty air.

I carefully made my way upriver searching each likely looking pool methodically. I was using a long rod adopting Euro Nymphing tactics. I focused intently upon the bright orange leader as it entered the water tightening the line each time it twitched as the flies bounced the rocky riverbed.

Luck was certainly on my side for the flies came free each time they snagged the bottom. And even the trees failed to rob me of the expensive nymphs that were tied to gossamer thin 3.5 b.s fluorocarbon that tested my ability to focus through lens of recently prescribed varifocals.

As I wandered the river bank I observed the occasional wren flitting through the branches and the ever present red breasted robin.

A buzzard mewed above the trees and cock pheasants strutted arrogantly in the frosty fields safe for a few days now and with just a week of the shooting season left likely to survive into the warmer days of Spring.

I peered into the flowing water hoping to glimpse my quarry but the river seemed devoid of fish. I knew that grayling were present yet connection seemed less probable as the number of fruitless casts mounted.

I flicked my flies into another likely spot struggling to see the leader as strong sunshine shone into my face. I perceived the pausing of the line and lifted the rod to feel the magical and delightful pulse of life. The grayling gyrated strongly in the water and I took a step downstream releasing the net from my back in anticipation. The prize was just a few inches from the nets frame when the hook hold gave, the silver fish disappearing back into the clear tumbling water.

Would this be my only chance? Grayling are shoal fish so I figured that there could be more in this small pool. I retraced my steps dropping the flies into the pool again. After a couple of casts, the line tightened and after a short tussle I netted a grayling of perhaps 8oz.

I admired silver flanks and crimson dorsal fin, grabbing its portrait before letting it flip away into its home water.

I fished on contentedly a blank averted and confidence restored so that I fished with belief and conviction. Covering some promising lie’s, I strolled until I came close to the top of the beat.

Woodsmoke drifted up from the chimneys of cottages across the valley. I savoured the rural scene as I worked my way back downstream revisiting promising pools. In a deep slowly moving pool the leader stabbed down and once again I connected to another grayling. This one was bigger than the first a fish of perhaps 12oz that was once again admired before slipping back into the Haddeo.

As the sun began to sink lower into the sky I fished on down with no further action. I reached the bottom of the beat and clambered over a style that allowed access to the river beside an old stone bridge. I descended into the river and waded beneath the old bridge contemplating the cars above racing around the troubled modern world.

I arrived back at the car poured hot coffee from my flask and reflected upon another perfect day beside a meandering stream.