It’s almost Mid-May and the evenings are long with dusk now lingering well past 9.00pm. I always seem to be caught out not fully appreciating the onset of Summer realizing all too soon that it’s getting towards the longest day and that those days will once again start to shorten. In the words of that Pink Floyd song;

Staying home to watch the rain

You are young and life is long

And there is time to kill today

And then one day you find

Ten years have got behind you

No one told you when to run

You missed the starting gun

I arrived at the fishing hut early evening pleased to be at the beat for only the second time this season. I was half expecting there to be another angler fishing but I had the fishing to myself. I had brought my salmon rod and a light trout rod just in case the trout were rising and could be tempted on a dry fly.

The river looked to be in fine fettle a perfect height and good clarity. I watched the river carefully for signs of life but no fish moved.

I left the trout rod in the hut and approached the water’s edge extended a line across the water and drifted a silver stoat’s tail across the river. I made my way carefully negotiating the slippery rocks coated in slimy algae. My casting could be better I thought, no sweet rhythm this evening.

After a few steps I was startled by a head appearing just a couple of feet from the rod tip. The large otter rolled again a further few yards down river. There are some who curse the otter for it predates upon the salmon and sea trout. I take a slightly different view for whilst I fear for the salmon I accept that otters have hunted this river for centuries. There was once an abundance of salmon in this beautiful river more than enough for angler and otter.

I feel sure that if I had stood on this river bank just thirty years ago salmon and sea trout would be leaping from the water crashing back with loud splashes that would fuel the anticipation.

This evening the ever flowing river heads to the estuary and the ocean beyond. During my two hours I drift my fly in fading hope. There are no glimpses of silver, the river banks are lush and green. The scent of wild garlic drifts in the warm evening air. But despite the natural beauty all around I cannot help but dwell upon the lack of salmon and sea trout. As a young angler I assumed the salmon and sea trout would always run the river or at least throughout my lifetime. Sadly I realize that this may not be so as the actions of mankind decimate the natural world and in particular the rivers those arteries of the land.

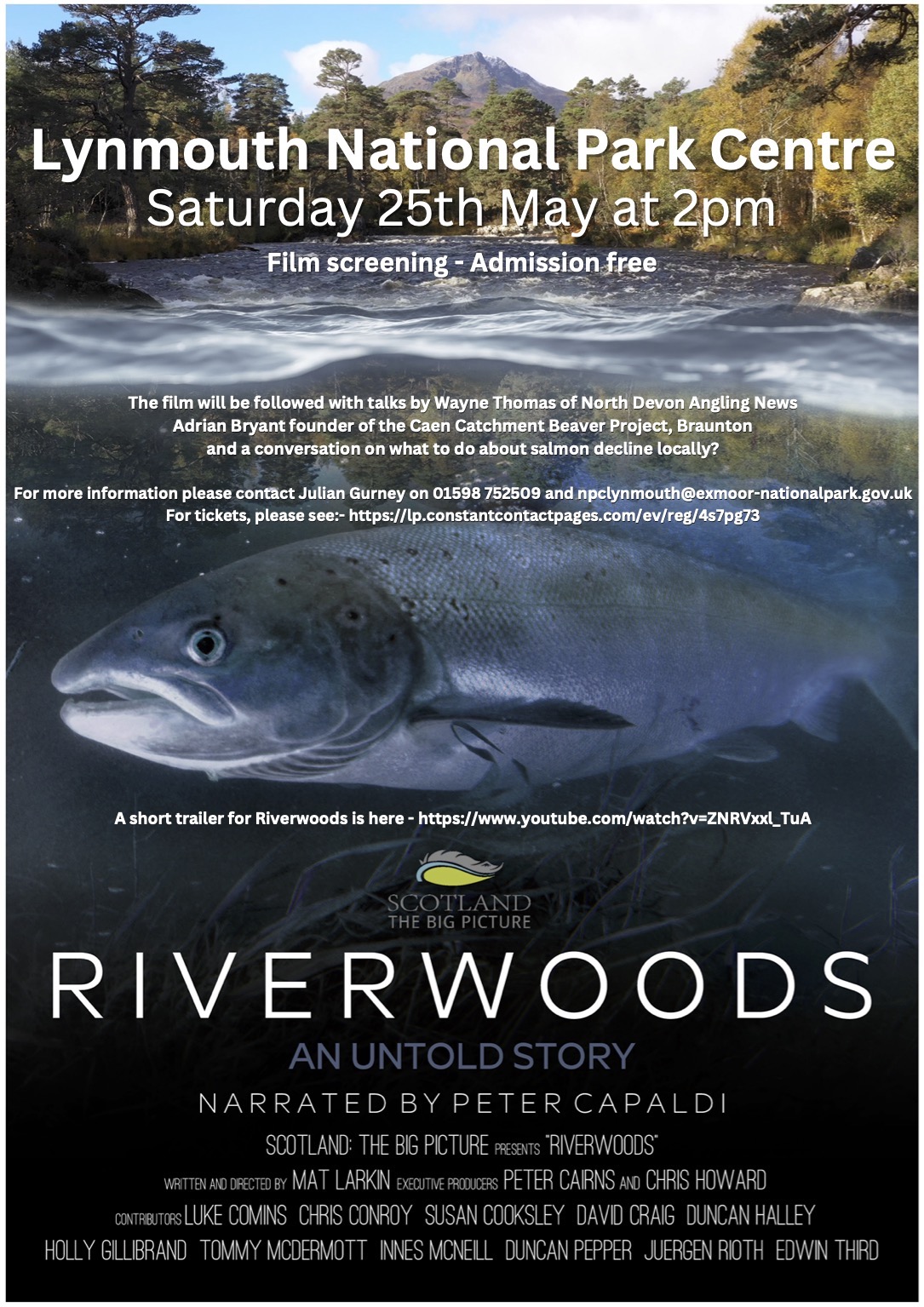

In recent months I have been involved in the screening of the film Riverwoods to audiences across North Devon. The film suggests solutions to the demise of salmon. After the film I give a presentation about salmon decline in the South West and beyond. I talk of the plight of salmon, their decline in my lifetime and suggest ways that we can all delay their route to extinction.

I ponder upon the salmon’s plight as I pack away my tackle. The angler, the otter and the salmon are all perhaps on borrowed time unless we act to bring our rivers back to life.

As I step from the River I again see the Otter heading back up river where Henry Williamsons fictional Tarka may well have swum. I read the tale recently a book that records a time of abundance full of cruelty but all within a more balanced natural world before a burgeoning population brought us to our present place in history.

And you run and you run to catch up with the sun but it’s sinking

Racing around to come up behind you again

The sun is the same in a relative way but your older

Shorter of breath and one day closer to death

My next trip to the river will be to the higher reaches where the water still glistens running clear with vibrant beautiful crimson spotted brown trout in abundance.

Fishing is good for the soul and we really need to celebrate the wonderful nature that we still have around us. The fleeting glimpse of electric blue as a kingfisher flashes past. The swooping swift, the evocative call of the cuckoo, the cheerful chirp of the chiff chaff.

That great Countryside writer BB’s books include the rather poignant words.

The wonder of the world, the beauty and the power, the shapes of things, their colours, lights and shades, these I saw, Look ye also while life lasts

I wonder what BB would make of today’s world?

Strange game this fishing lark and angler’s fishy targets that vary considerably. Bream are a species that are loved by some and loathed by others. My own feelings on bream go back a long way and they are a fish I have mixed feelings for rather like eels. Small skimmers are slimy creatures only worth catching during match’s and a complete nuisance when targeting bigger fish. Eels are much the same with slimy bootlaces tangling the tackle whilst snatching bait offered to a more worthy specimen.

Strange game this fishing lark and angler’s fishy targets that vary considerably. Bream are a species that are loved by some and loathed by others. My own feelings on bream go back a long way and they are a fish I have mixed feelings for rather like eels. Small skimmers are slimy creatures only worth catching during match’s and a complete nuisance when targeting bigger fish. Eels are much the same with slimy bootlaces tangling the tackle whilst snatching bait offered to a more worthy specimen.