Many thanks to Richard Wilson for once again sharing his writing on North Devon Angling News. This months article is more than a little sobering as we can see the drama unfolding on our screens each day. These are indeed interesting times to live in and the symptoms are to be seen all-round.

Sweet memories: The high-summer days as July drifts into August. Cole Porter’s lazy, hazy, crazy days as time sprawls soporific in the warming sunshine. The beer and wine on ice and all gently fusing in the company of old friends. A river burbles nearby while an occasional splashy fish shows midstream. What could be better?

So that was going to be my theme for this article: Chilled booze, cool friends and throwing the dog in (there’s no more enjoyable way to catch summer fish – more on dogs below). A comforting vision of an unfolding August caressed by warm nostalgia.

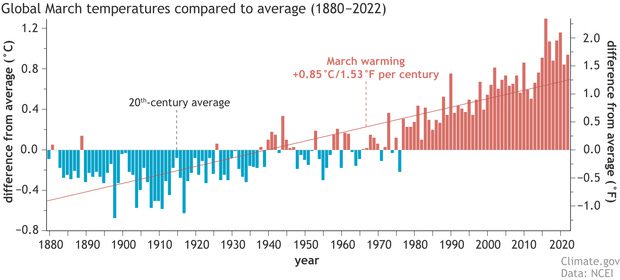

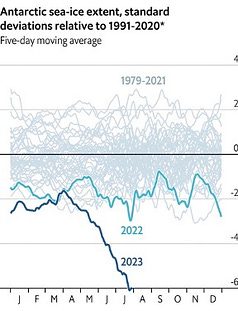

Then a lot of other stuff happened pretty much everywhere and all at the same time. Canada’s forests caught fire and New York choked in the smog, the US south and west and most of Europe wilted in record-breaking heat, the North Atlantic and the seas around Florida simmered, a lot of places flooded and England’s rivers became fetid, drought-stricken trickles of raw sewage. And, meanwhile, algal blooms suffocated seas and lakes worldwide. These events are global, national and in my garden. So writing a piece romanticising warm rivers and slow, soporific summer afternoons suddenly seemed clumsy.

Instead, an old curse rings in my ears: ‘May you live in interesting times’. Because, it turns out, I do. In the first week of June and in the far north of Scotland, these interesting times came to get me. Fishing was stopped on my trip to the River Oykel because the water temperatures were too high. In early June! This is a time of year and latitude when spring should be alive with bird song, wildflowers and new beginnings. Instead, we sweltered. And as we did, more bad news arrived from abroad as El Nino started flexing its muscles. It’s arriving this autumn and, by all accounts, is a bad one. And bad in this context means trillions of dollars will be lost and a lot of people will die.

We now have a lethal mix of weather and climate change, each piling misery on top of the other. As a brief aside, weather is what happens and we have climate change because if we fill the atmosphere with 200 years of industrial-era pollution it will get warmer and choke. Just as our rivers choke on shit if we keep dumping long after we should have stopped. Some people still have trouble with this idea.

That most stalwart conservative publication, The Economist, reports that a heatwave is a ‘predatory event that culls out the most vulnerable people’ – the poor and the old. They add, “It slaughters silently, snuffing out more American lives each year than any other type of weather”. It used to be cold that killed the most. Climate change, says The Economist, is deadly. I find it strange that some of the most at-risk social groups are the most strident climate change deniers (a predominantly 65+ demographic).

There are 2 possible explanations for what is happening this year, and they’re both deeply worrying. It might be a blip that fits within the warming new-normal we live with or, perhaps, a more alarming acceleration in the underlying rate of change. Whichever it is, we’ve arrived in uncharted territory. Agriculture and everything we think of as modern humanity started about 10,000 years ago and has thrived during a period of climate stability. The Earth was last this hot 125,000 years ago. So while an extra degree or two might look to some like a small twitch on the global-average temperature gauge, it isn’t when you look at the increasingly wild regional climate fluctuations – as can be seen by anyone who follows the news. And so far the scientists have been right; recent temperatures and their consequences are as most climate models projected, albeit at the hotter end. What happens next is less certain.

Life is unlikely to come to a juddering halt, but it will get a lot more difficult. As ever, there’s a caveat: Reputable research published this month suggests that the deep Atlantic circulation (AMOC), which is associated with the Gulf Stream, could fail within 3 years, altho’ that’s most likely to happen mid-century (Copenhagen University). This would indeed be catastrophic.

And look at the language we’re using. A phrase that used to hover in the margins of the climate debate has gone mainstream: the positive feedback loop. Forest fires release CO2 which warms the planet causing more fires. The same applies to methane release from thawing tundra. There are also more frequent sightings of the words runaway positive feedback loop and tipping point.

In the face of this year’s extreme weather and its major economic impacts, kicking these issues down the road in the hope that something good will happen looks increasingly futile. That thought is from the Chatham House think-tank, which isn’t given to hyperbole.

At this point, I’d like to interrupt myself briefly to ask you a question or two: How many days fishing will you lose this year because our rivers and lakes are too warm? Will next year’s fishing be better or worse? How are the redds faring?

It might seem a bit of a leap from global catastrophism to a riverbank with rod in hand, but we’re all going to have to adapt (I wrote about mitigation HERE ). Call me Nero if you like, but we humans are really good at adapting. And we’re going to have to get a lot better at it in all sorts of ways.

So, this may be me fiddling while Rome burns, but I’m hoping the rate of change is going to be at the slower end of predictions. If so, I’ll need that dog I mentioned earlier. Because the simple truth is that even in the good old lazy-hazy days you couldn’t do proper slow summer fishing without a dog and, one way or another, the dog had to go in. And where once this would have happened in late July or August, nowadays May and June are the new dog-days of summer. So the dog is my consolation; a small adaptation I can look forward to and that will keep me on the bank.

Here’s how it works: The writer Ed Zern, a man of quick wit and impeccable unreliability, told of an old timer he knew back before the Second World War. A man who claimed that, if fishing a summer pool with not a salmon to be seen, would turn his attention to catching a couple of trout for the pot. His approach was unorthodox. He would tie a 6ft leader, a dropper and a couple of wet flies to his dog’s tail, and then throw a stick across the pool. The dog, of course, was thrilled to be in the chase and the angler scored two wins: The dog stirred up the salmon and improved the fishing, and also brought back a brace of equally agitated trout for supper. What happened if the dog got into a 30lb salmon is not recorded. American salmon, according to Zern, think dogs are seals. And the caveat? As said, Zern was a very unreliable witness and the trout part of his story is unusually fishy.

This also works at night, which is another cool advantage in our brave new world. Indeed, it was at night that I discovered just how effective a dog can be and why this works (even though no dogs were involved).

Late one summer’s evening, shrouded in the gloaming, I headed out on foot for a night’s Sea Trout fishing. It was that magical hour when day hands over to night and the owls, small scurrying creatures and chuntering water replace the daytime clamour. The river was low, as is the new normal (when not flooding), but Sea Trout, as they say, will run up a wet sack. The night was charged with promise.

I moved slowly up the bank, careful to arrive at my pool without spooking the fish, and then settled down to wait for darkness to wash over the river. Only once all is crow-black, bible-black, (Dylan Thomas-black) would I start to fish.

This night was different. Through the half-light, I could see a pair of otters playing exuberant otter-tag and working their way upriver towards me. Once in my pool, they started the serious business of hunting and I had a ring-side seat as two of nature’s most beautiful creatures plundered my fishing. Time flowed by and I don’t know how long I sat enchanted and uncaring that my night’s sport was being trashed before my eyes. This was already among the most memorable of fishing nights, and I was still on my backside.

Eventually, they picked up my scent and in an instant were gone. The pool stilled and the darkness settled back around me. My senses strained, but nothing moved.

I gathered myself, my rod and my minimal kit and stepped down to the river to cast a line. It felt like a futile gesture, but it was a beautiful night and I was reluctant to leave.

The line kissed the water and the pool burst into a mid-summer’s night madness. I caught an 8lb sea trout with my first cast and another of 6lb with my third. These were big fish for this river – much bigger than the expected 1-2lb schoolies. The otters had disrupted the pool and I had reaped the benefit by dropping my fly into the chaos.

And then, just as suddenly, the fish turned off. There were no fishy splashes on the margins of my senses. Just nothing – the pool had died. The fish frenzy had lasted for the 30 minutes or so it took the remaining sea trout to slough off the otter terror and revert to their normal, elusive behaviour. It was as though the otters had never existed

How long was I there that evening? I don’t know. Time had frozen into the very essence of slow fishing, which was mostly no fishing at all. The next day I told the riverkeeper my story. He smiled and said, ‘When all else fails, throw the dog in’. It’s an old saying that happens to be the just about only piece of fishing wisdom that actually works – and climate change will have to get worse before it fails.

In the UK, dogs are otters. In Canada maybe they’re bears. Zern says they’re seals.

And climate change is global, so if we keep going the way we are there will be no salmon to throw the dog at.

______________________________________

Thank you for taking the time to read my work. It really helps me if you can do some, or even all, of the following:

Tell others I’m here: via sharing on social media.